My First OKRs

UPDATE - 24 Mar 2021: A revised version of this post has been published at What Matters.

A few weeks back, Ryan Panchadsaram & Elizabeth Dunne from What Matters asked me about my first OKRs. Here’s the video and the full story below.

In mid 2015, I came across a couple of blog posts about OKRs and got excited. I was helping the UK’s Government Digital Service to scope their complex change portfolio and secure nearly £500m in funding to continue its digital transformation work and ultimately make the UK the world’s most digital government in 2016.

OKRs were a perfect fit for helping teams to scope out their ambition.

By the end of 2015, I’d seen how OKRs could help teams to focus and reach for the stars. Now, I wanted to know how they could help me. Like many folks, I’ve been known to set New Year’s goals so when 2016 arrived, I jumped on the opportunity to set some personal OKRs.

My wife and I had recently moved, we had an energetic 3-year-old, and I’d been working…a lot. All of this had put a strain on our relationship, my friendships, my sleep, and my physical health. In short, life had room to improve.

OKRs to the rescue…maybe?

I sat down one Saturday morning in early January with my trusty Sharpies and sticky notes and drafted what felt like some sensible OKRs. I carefully hand-wrote them on a sheet of thick paper and hung them on the wall.

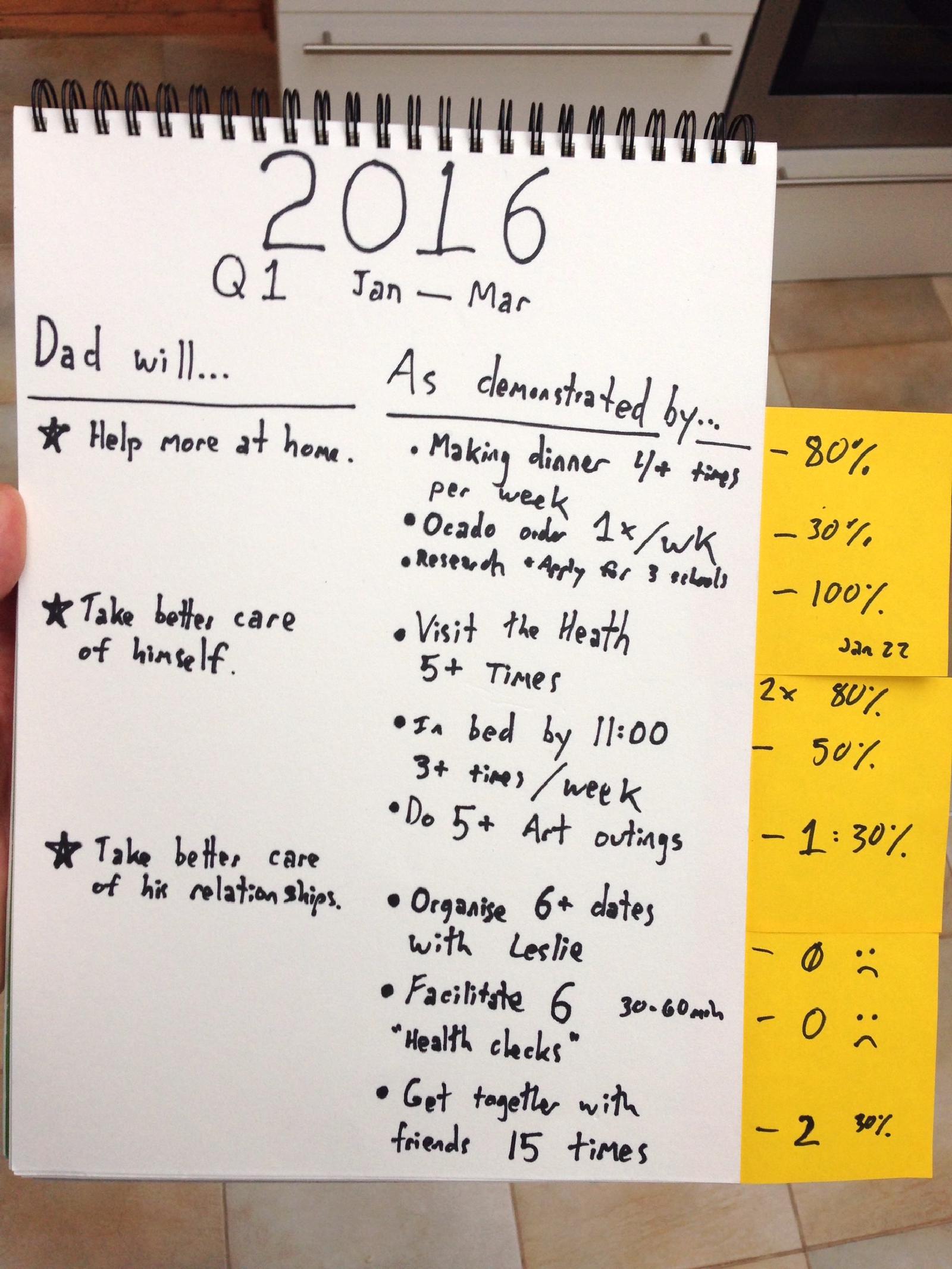

They looked like this:

Later I started doing regular checkins and putting sticky notes on the side to track my progress (I hadn’t, yet, started measuring confidence). Later, I developed a simple tracking tool I made in Google Sheets but sticky notes were a good start!

I missed most of my targets. OKRs are meant to be aspirational, right? Looking back, the bigger issue is that these key results were really initiatives in disguise. They gave me things to do but doing those things didn’t actually demonstrate that I had reached the objective. It’s useful to remember that OKRs define a measurable, desired end state but not the specific path you will take to get there. OKRs are for alignment, not project management.

The objectives, themselves, used weak language. They were written in the third person and used words like “help” and “more” or “better”. They would’ve been more powerful if I’d rephrased them to say:

This quarter I will…

- Be an outstanding life partner

- Take exceptional care of my health and wellbeing

- Build great relationships with my friends & family

I might have measured these by surveying my wife (uncool), surveying myself (I’ve done this, actually… and it works), and surveying my friends but, in this case, measuring how many times we hung out felt like proof enough.

Get better; not perfect

Despite not “achieving” all of my key results, this was a valuable exercise. I learned how to strengthen the language around objectives, I realised that key results should be measurable outcomes (not tasks) and, most importantly, I realised that OKRs could be a useful tool for helping me to focus my efforts and improve my quality of life (even when I fell short). My wife and I started talking more about what would make life better. We started behaving differently… we got more sleep.

And over time I realised the importance of tracking confidence and creating key results that were actually results (not just tasks to have done).

If you’re wondering how to get started with OKRs, and don’t feel ready to experiment with your team(s), take a look at your personal circumstance, dig deep, write a few things down and try them out for a few months. If nothing else, it’s a great reminder that a thing worth doing is worth doing badly and practice makes better.

What were your first OKRs? Let me know!